BY BEENISH AHMED

“What happens to a dream deferred?” Langston Hughes asks in his poem, “Harlem.” Although he delivers a litany of possibilities, he does not presume to know the answer. Lucky for us, he did not defer his own dream.

Despite familial pressure to assume a more lucrative line of work, Hughes pursued his passion for writing and delivered some of the country’s best known meditations on black life, racial inequality, and yes -- the importance of a dream undeferred.

Now that the nation is again watching what New York Times reporters have called a “a recurring, seemingly inescapable tape loop of American tragedy” in which outrage over the killings of unarmed black men by white police hours plays on and on, Hughes’ unstilted commentaries on race have become only more prescient.

To understand the context in which Hughes penned some of his most revered works as well as the conflicts that underlined them, I spoke with Hughes’ biographer and emeritus professor of English at Stanford University, Arnold Rampersad.

The questions below are an abbreviated form of our conversation, which has been edited for clarity.

LANGSTON HUGHES IS A POET WHO EVERYONE SEEMS TO KNOW AND YET DOESN’T REALLY KNOW. MUCH OF THE WORK WE READ ABOUT HIM AS “THE DREAM KEEPER” AND NOT A SOCIAL JUSTICE ADVOCATE. I CAN SAY FOR MYSELF THAT MY FIRST BOOK OF POETRY WAS A COLLECTION BY LANGSTON HUGHES FOR CHILDREN WHICH I BOUGHT IT AT A SCHOOL BOOK FAIR IN MAYBE THE THIRD GRADE. WHY HAS HE BEEN STRAPPED WITH THIS SOFTNESS WHEN SO MUCH OF HIS POETRY IS ABOUT HARD REALITIES?

I think we think of Hughes as “soft” because there’s a quality of intimacy and tenderness, a sort of person-to-person feeling that is present in so many of his best-known poems that we tend to think of him as a poet whose work is easily accessed. The language is not difficult. You don’t have to wonder what phrases or words mean as you do in the work of so many modern poets. There’s not a sense of a poet or an artist operating in a sort of opposition or a kind of contest with the reader. You have a sense almost all the time of someone in deep sympathy with the reader starting with the sympathy for understanding language. But on the other hand, Langston can be extraordinarily tough. If you look at the poems he wrote in the 1930s during the Depression and if you look at his many poems about civil rights in ‘40s and then later on, you see that he is capable of expressing qualities such as anger, rage, or anything but soft. And when you put it all together then, you have a picture of a very balanced human being as a poet and that’s why I think he’s so important to so many people.

I, Too

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,"

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

LANGSTON HUGHES’ POEM ‘I, TOO’ IS ENGRAVED ACROSS THE WALLS OF THE NATIONAL AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND CULTURE WHICH OPENED LAST MONTH IN WASHINGTON, DC AND IT WAS ALSO PRINTED ACROSS A FULL PAGE IN THE NEW YORK TIMES. CAN YOU TELL ME A LITTLE ABOUT THE CONTEXT OF THE POEM AND ITS PLACE WITHIN HUGHES’ BODY OF WORK?

Hughes wrote ‘I, Too’ when he was stranded in 1923, I believe it was, in Genoa, Italy. He had spent several weeks in Europe, weeks that were important to him, working in a jazz nightclub and so on, and then he had traveled a bit with Professor Alain Locke who is one of the major scholars, presences, philosopher presences of the Harlem Renaissance. And then he had lost all his money and had his passport stolen and he was stranded for many weeks in Genoa while he was trying to get home to the United States, to his mother, to his friends, an to his life there, he formed a bond with a number of the seamen and other people from around the world who were in desperate straights in that port city.

He also had to endure the fact that several ships came into port heading to the United States, but their captains would not take Hughes on as they were prepared to do for white people who had been stranded in one way or another and so he watched the ships sail off to America without him while he remained close to extreme hunger, in many cases, in Genoa. He had previously published almost all of his poems in The Crisis magazine, the magazine edited by W.E.B. Du Bois for the NAACP in New York. And he sat down one day and I think poured out his sense of hurt at being treated in this shabby way by his fellow Americans and also his confidence that this condition, this state of affairs would not last forever, that one day, the country would recognize that people who looked like him posed no threat and in fact were the darker brother, the darker sibling, and that people in America would one do be ashamed of the way that blacks were being treated, and had been historically treated through slavery and Jim Crow and so on.

The poem was deeply heartfelt and he sent it off to The Crisis, hoping to get a little bit of money, maybe $10, that would enable him to buy his passage home, but at the heart of it is this sense sadness, of sorrow, but also of great confidence in his people and in America. Of course you cannot read the poem without recognizing the voice of Walt Whitman, the great American poet of democracy in it. The trope of ‘I sing America’ is directly, almost, out of Walt Whitman and Hughes is aware of that. He wants to align himself with Walt Whitman [...] and insert himself into the discussion as representative of the darker peoples, the darker brothers and sisters and create a poem that would move people and that people would remember. I think he succeeded magnificently in that way.

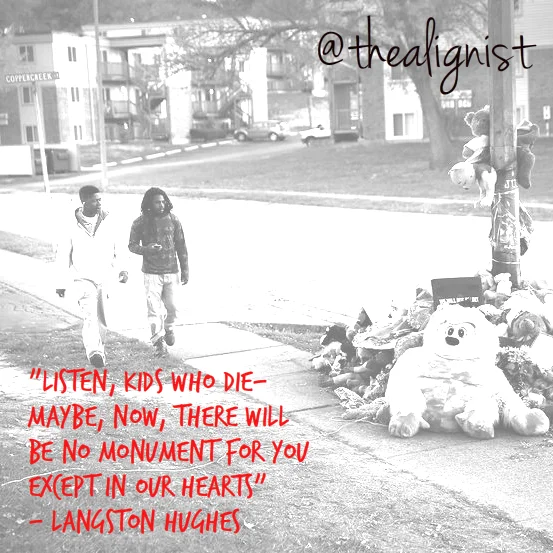

I SHOULD SAY THAT THE ATTENTION FOR ‘I, TOO’ CAME JUST AFTER THREE SEPARATE INCIDENTS IN WHICH WHITE POLICE OFFICERS SHOT AND KILLED UNARMED BLACK MEN -- AND IN ONE CASE, A 13-YEAR-OLD BOY. HUGHES ADDRESSED POLICE BRUTALITY AND RACIAL PROFILING IN MANY POEMS. “WHO BUT THE LORD” AND “KIDS WHO DIE” HAVE BEEN PICKED UP BY BLACK LIVES MATTER ACTIVISTS BECAUSE OF THEIR DAMNING RELEVANCE TO RACIAL STRIFE TODAY. DID THEY HAVE A SIMILAR ROLE WHEN HUGHES WROTE THEM?

I think Hughes always intended a great number of his poems to be poems of protest against harsh conditions in the South in particular, when he was growing up, when he was a young man, and throughout his lifetime, really, because the South continued to be a place [of racial intolerance] until the very end of his life in 1967. The conditions for blacks -- whether they were trying to vote, or use public transportation, or go to better schools or what have you -- were just horrendous [...]. Many of his poems speak directly to that question and they also speak directly to the question of armed power or the threat posed by lynching in particular, [and generally] the threat of violence towards people of African-American descent. [...] So much of his poetry has to do, to use the current term, with black lives mattering, and the need to stand up to people who deny the principle that black lives matter.

More than 70 years have passed since civil rights activist and poet Langston Hughes wrote his chilling poem "Kids Who Die" on the horrors of lynchings during the Jim Crow era. Now, after the police killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Keith Scott, and so many others, Hughes' words still ring true today.

YOUR BIOGRAPHY OF HUGHES WAS CRITIQUED BY HILTON ALS OF THE NEW YORKER FOR PRESENTING AN ASEXUAL PICTURE OF HUGHES. AS HE PUT IT, YOU TOOK AN “I-DON’T-KNOW-ANYTHING-SPECIFIC-ABOUT-HIS-ROMANTIC-LIFE” APPROACH TO HUGHES’ SEXUALITY. JUST AFTER THE REAL IDENTITY OF ELENA FERRANTE WAS REVEALED BY AN ENTERPRISING REPORTER DESPITE HER PLEAS FOR PRIVACY -- DO YOU THINK THE ISSUE OF HUGHES’ SEXUALITY SHOULD BE GIVEN THE PRIVACY HE RESERVED HIMSELF OR DOES THE READER DESERVE TO KNOW THIS INTEGRAL PART OF THE POET’S IDENTITY?

I think there are many reasons that if Hughes were gay, why he would not want to advertise that fact, least of all the fact that in many places indulging in homosexual activity was a very serious criminal offense and that his very existence as a publishing poet would be absolutely threatened if that were well known. He lived in different times from ours. The whole idea of a movement [in support of] lesbianism or homosexuality, this is all very recent. Times have changed, the country has changed, he was a part of that change, but as I said, there are many solid, sound reasons why he couldn’t protest against conditions [for LGBT people or] assert himself in certain ways that perhaps he would have wanted to.

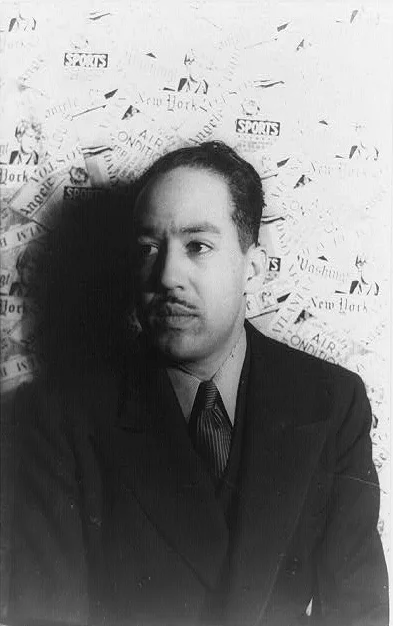

LANGSTON HUGHES SITS FOR A PORTRAIT BY CARL VAN VECHTEN IN 1936. IMAGE VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS.

I think the readers ought to learn about any aspect and every aspect of Hughes’ life and personality with which we can speak with authority. My position has always been that Hughes might have been gay, I’ve even switched to the idea that Hughes was probably was gay, but as a biographer I always insisted that with any question with Langston Hughes one had to have direct evidence that he was gay.

I point out again and again that I interviewed many people who knew Hughes, and were themselves gay, and had been openly gay since the 1920s and they either could not say that Hughes was gay or they deny that Hughes was gay. I found no one who could tell me that Hughes was gay because of such and such and such. As a scholar, it was not appropriate for me in the face of that body of evidence to come out and assert that Hughes was gay but I think it is a perfectly legitimate question, I think it is a distinct possibility that Hughes was gay, I’m just simply operating by a different set of standards, -- as if Hughes were in a court of law as it were, and evidence was being presented -- but other people are free to say whatever they like and to make broad assertions about Hughes that they cannot support via evidence if that’s what suits them. More power to them if that’s what they want to do. It’s not appropriate for a scholar to assert things not only for which there is no evidence but for which there is in fact contrary evidence. [...] People like Carl Van Vechten or Bruce Nugent who knew Hughes starting in 1924 and who was gay even in the 1920s, he was one of the people I spoke to who ventured the opinion that Hughes was not gay, so I don’t know what one does in the face of that kind of evidence, but for me it had to be respected and honored even as I respect and honor the right of other people who think that they sense in Hughes the qualities of a gay and then assert that he must have been one. That’s fine with me.

I’d ask myself, ‘Am I ashamed of the idea that Hughes might have been gay?’ and I had to say, ‘No, I don’t think so at all.’ In my biography, which is pretty extensive, and pretty old by this time too, I reveal many unsavory things about Langston Hughes, many facts about Langston Hughes that he would never have wished to see in print, political, but also sexual. So I would not have been in any way disinclined to write about Hughes as a gay man if I had found evidence -- evidence -- that he was gay, but I didn’t find any and therefore one can only suppose and hope and that’s fine too.

Cafe: 3 a.m.

Detectives from the vice squad

with weary sadistic eyes

spotting fairies.

Degenerates,

some folks say.

But God, Nature,

or somebody

made them that way.

Police lady or Lesbian

over there?

Where?

IN 1925, WHEN HUGHES CAME BACK TO NEW YORK 1925 AFTER TIME SPENT ABROAD, HE FOUND BLACK MUSIC AND DANCE ALL THE RAGE AMONG WHITE SOCIETY IN THE CITY. HE WROTE IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY THAT, "IT WAS THE PERIOD WHEN THE NEGRO WAS IN VOGUE." IN SOME WAYS, IT SEEMS THAT PERIOD NEVER ENDED. BLACK CULTURE CONTINUES TO BE IN VOGUE AND YET THERE IS A MOVEMENT TO MAKE BLACK LIVES MATTER. AS SOMEONE WHO USED BLACK VERNACULAR AND JAZZ RHYTHMS IN HIS POETRY AND WATCHED BOTH THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT AND RACE RIOTS ENGAGE THE NATION, HOW DID HE NAVIGATE THE DICHOTOMY OF SEEING HIS CULTURE COME TO BE CELEBRATED WHILE BASIC RIGHTS REMAINED ELUSIVE?

I would call into question the idea that black culture was genuinely in vogue. Hughes also says about the Harlem Renaissance that if you [asked] ordinary black people in Harlem if a renaissance was going on, they would look at you and laugh because their experience of life was much harsher.

A small aspect of black life, black culture was in vogue among a small number of generally privileged people and that was part of the problem. If you look at movies that involved depictions of black life, [however] you see how terribly, how poorly terribly black life is and black lives were. Black people were butlers and maids and kowtow to white people and so on. So the idea of black culture being celebrated is just not [true]. In fact, it is very much a part of the problem that Hughes and others were trying...to change. To change the way America saw as more than just shuckers and jivers and dancers and jazz musicians [to] people with a past and a spirituality to match other qualities.

He was always aiming for this sense of balance which was so terribly missing from the white American conception of what blackness was and is. It was always a struggle. It was always uneven. But this business of black lives matter that they’re dealing with now, black lives mattering has been a contention within the black leadership for at least 100 years [...].

An effort to bring a dignified understanding of black lives and culture to the forefront so the fight continues as the saying goes. The struggle always continues and this is but the latest phase in a struggle that so many people have been involved with in the aftermath of slavery, and in which Hughes was one of the leading voices, operating in his own fashion, in his own way, as we’re all called upon to act in our own way contributing as we can...with the one goal in mind: ultimate social justice.

DID THE ACCLAIM HUGHES RECEIVED FROM WHITE CRITICS INFLUENCE HIS PRESENTATION OF BLACK LIFE? I’M THINKING HERE OF THE CONTROVERSIAL WORK, FINE CLOTHES TO THE JEW, WHICH WAS LAMBASTED NOT ONLY FOR THE TITLE, WHICH HUGHES SAID HE REGRETTED, BUT ALSO FOR ITS DEPICTIONS OF POOR BLACK PEOPLE WHICH BLACK READERS CALLED A "DISGRACE TO THE RACE."

I would contest [the claim] that Hughes’ work was embraced by white people. I think it was embraced by a small portion of white people. We have a way of quantifying these things: how many books did he sell [reveals] how popular he was really in the way that counts for people who write books...He was always a modest seller. Did he pack audiences when he gave poetry readings? Well no, not exactly. He attracted a lot of black listeners who loved his work, who loved what he was doing in altering the image of black Americans, but only a few liberal whites recognized what he was doing and applauded [his work]. For him, it was always, always a struggle for an audience and it affected what he could do in terms of politics. He was very bold in adopting pro-Socialist politics in the 1930s, but when those politics threatened his livelihood, his ability to continue as a functioning writer writing about black people, he had to back off and he did back off. He didn’t back off from arguing for the basic civil rights of black people, but he did back off on how radical black people could be especially when one thinks of being radical as being pro-communist or pro-socialist. He definitely backed off, had to back off and did, to preserve his self-appointed role of being the poet of the black experience.