BY BEENISH AHMED

On April 24, 1915, the Young Turks of the Ottoman Empire rounded up hundreds of Armenian intellectuals and community leaders in Constantinople (now Istanbul). They were later forced out of the country. Their exile began what is now considered the first genocide of the 20th century.

Lola Koundakjian, sits beneath a portrait of her father in her New York City home. Photo courtesy of Koundakjian.

According to the International Association of Genocide Scholars, “More than a million Armenians were exterminated through direct killing, starvation, torture, and forced death marches.”

On the centennial of these events, THE ALIGNIST reached Lola Koundakjian, an Armenian poet and the founder of the Armenian Poetry Project to share her thoughts on the poet’s role in documenting such horrors and growing up with the legacy of loss.

“I don’t have family histories beyond 100 years. No mementos, family bibles, pictures, stories,” she said in an email to THE ALIGNIST. “I am alive because of small, human miracles […] All my grandparents were orphans. I don’t know much about their past but they talked about the Genocide all the time.”

A century later, Koundakjian works to foster remembrance through her own work and the work she features through the Armenian Poetry Project. What follows is an email conversation with her.

1. HOW AND WHEN DID YOU BEGIN TO WRITE POETRY?

I have always loved poetry, but in high school and university I was encouraged to pursue visual arts. I got an MA in history and wrote about the Armenian potters who settled in Jerusalem during the British Mandate. I read a lot, and then one day, I decided to promote Armenian poetry. Over the course of doing research, I took out my old notes, the early poems, re-read my short stories, including the science fiction ones, and started writing. By the way, the only university books I have kept are my poetry course books.

2. WHAT MOTIVATED YOU TO START THE ARMENIAN POETRY PROJECT?

I thought it was important to promote a culture which is not as well know as its western counterparts. The language is spoken mostly by Armenians, and a small group of scholars and translators. I felt the need to share its beauty with the world.

"They died"

by Lola Koundakjian

They died, father, mother and daughter

And the newspapers reported it

But how many others died

Alone.

They were killed, father, mother and children

And the neighbors witnessed it

But how many others were killed

Alone.

They were burned, sister and brother

And the parents saw it

But how many sisters and brothers

Were burnt, alone.

They were buried, Armenians, Kurds

Arabs, other peoples

But how many others were buried

Without a witness.

3. YOUR POEM "THEY DIED" SPEAKS TO THOSE WHO DIED -- OR, PERHAPS WERE KILLED -- ALONE. AMONG THE MANY HORRORS OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE, WHY DID YOU CHOOSE TO HIGHLIGHT THAT OF THE SOLITARY DEATH?

There are many testimonials about the mass murder of Armenians. The ones that reflect my mother’s side of the family include the march through the desert of Der Zor. There are no graves for the hundreds of thousands who died in that desert; they dug and placed bodies then covered them, sometimes in mass graves. My grandparents arrived in Aleppo, Syria, where they lived in orphanages. My grandmother testified in a video recording that she remembered seeing her sister and mother die.

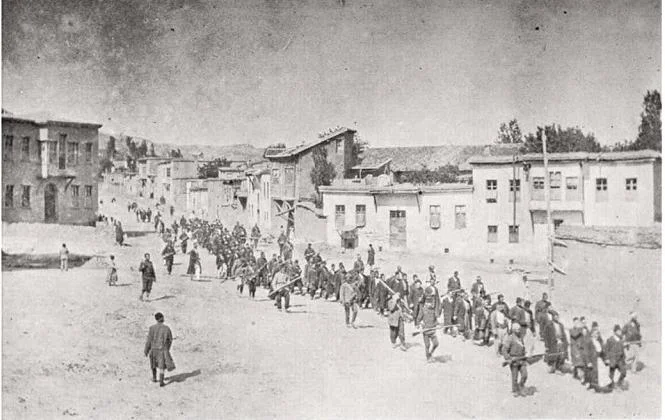

Armenian civilians were marched by Ottoman soldiers to a prison in Mezzireh (now Elazig) in April 1915. Photo licensed through Wikimedia Commons.

4. WHAT DO YOU SEE AS THE ROLE OF POETS IN "BEARING WITNESS" TO ATROCITIES SUCH AS THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE?

I disagree that poetry is disconnected from real life or the world. Poets are very much connected with every day occurrences to larger events such as wars and natural disasters. I didn’t invent the term “Bearing witness;” we have many great poets around the world working very hard to bring attention to causes, which are not always covered in the news.

"Keeper of the Bones"

by William Michaelian

The old man told me

he himself had died

a long, long time ago.

He pointed to a distant plain,

a tide of earth that once

bled mountains of their loam.

The harvest there is rich,

he said, it never ends,

the fingers, limbs, and skulls.

In the sun beside his hut,

an ancient cart trembled

beneath a village of bones,

A genocide of sightless eyes

that sang the wind

proud and low and long,

An insane congregation

borne by wooden wheels,

a cemetery without a home.

From out across the plain,

the old man touched

my fleshless, bleached-white arm.

From out across the plain,

I too became

a keeper of the bones.

5. HOW HAS DISTANCE AND DISLOCATION ALTERED HOW YOU SEE ARMENIA IN YOUR WRITING? HAS IT CHANGED HOW YOU READ ARMENIAN WRITING?

I have never lived in the lands which were part of our kingdom or present day Republic [of Armenia]. I am from the Armenian diaspora. As the descendants of those deported, or living far from the homeland, our sentiments are strong with longing and trying to keep the culture alive. Today, it is difficult to meet people who still read works in Western Armenian, which was declared as a language in grave danger by the UNESCO.

"GRANDCHILDREN OF GENOCIDE"

by Alan Semerdjian:

We think of bombfields and big when we think of genocide.

We think of mass cleansing. We think in holes. We think

the whole page. We think what’s under it, what they’ve been

covering up. We think there might have been people

in those whole pages.

We think of chambers when we think of genocide. We think

of people crying. We think of people climbing. We think of

people climbing and crying, crying and climbing. We think of both

people climbing and people crying. We think in chambers.

We think in those horrible chambers when we think of genocide.

Those horrible 20th century chambers.

When we think of genocide, we don’t think of mountains and deserts.

We don’t think of bazaars. When we do think of them,

we don’t think of young democratic people and pomegranates.

We don’t think of young democratic people with pomegranates

at bazaars when we think of genocide. We don’t think of them

next to our grandfathers. We don’t think of next to them.

Then there are young democratic people who don’t eat pomegranates

and don’t think of genocide. We don’t think of them either.

We don’t think of them when we think of genocide, but we do think

of moustaches. We don’t think of long and lovely moustaches,

but we think of moustaches when we think of genocide.

We don’t think of grandfathers plural or generations of grandfathers

before that when we think of genocide. But we do think of mothers.

And mothers before that. But we do think of mothers,

but we don’t think of women. We don’t think of women dancing.

We don’t hear the music when we think of genocide.

These things we think about and not hear when we think about genocide.

And we don’t think of civil war as genocide. We hear about it.

We don’t call in enough with such information.

We think about reconciliation, but we don’t

think about reconciliation when we think about genocide.

We don’t study the memorials, we don’t explain the play in papers,

we don’t shake hands and make up. When we think of genocide,

we do other things with our hands.

6. WHY DID YOU CHOOSE WILLIAM MICHAELIAN'S POEM "KEEPER OF BONES" AND ALAN SEMERDJIAN'S POEM "GRANDCHILDREN OF GENOCIDE" AS EXAMPLES OF WORKS ON THE GENOCIDE?

William, a west coast USA poet sent me his work early on when I started APP, where as Alan Semerdjian is a personal friend with whom I have read on stage on several occasions as he is based in the same city as I. Both William and Alan are like me, descendants of the Genocide. Their work resonates for me.

Greek and Armenian refugee children in the sea near Marathon, Greece after their departure from Turkey. The children -- all orphans -- had never seen the sea before. Photo licensed through Wikimedia Commons.

7. DO YOU THINK ARMENIAN POETS AND WRITERS FEEL COMPELLED TO DEAL WITH THE GENOCIDE IN THEIR WORK, OR IS IT ONLY NATURAL THAT THE SCRIBES OF A PEOPLE WOULD ENGAGE WITH ITS SENSE OF LOSS?

This question is often posed in other cultures as well. Every African-American has shared how they are compelled to write a “Coltrane” poem, or another dealing with their forefathers in plantations. I think all writers who are connected with an ethnicity feel compelled to write something about a collective past.